Copyright 2020

Greenstone Media Consulting, LLC

Greenstone Media Consulting, LLC

American Broadcasting Company

Seattle - 1929

Seattle - 1929

The Trial

Embezzlement calls to mind sneaky, hidden transactions with carefully doctored accounting records – but it wasn’t like that at all. Linden would often go to a teller at the bank and simply say he need $15,000 or $20,000 and the teller would advance the cash with a note of the transaction going into something called the “teller’s drawer”. What happened to the note beyond that isn’t entirely clear but the tellers seemed convinced that it was all proper. Sometimes funds passed into or out of a “suspense account” which was presumably an account that held a transaction until more formal accounting could be completed. Many employees of Puget Sound Savings and Loan seem to have been aware of these practices.

There was more than enough blame to go around. The state banking inspector, Wallace L. Nicely, was serving on Puget Sound Savings and Loan board while simultaneously serving as the regulatory official with responsibility for overseeing the bank. He was charged with both this having defrauded the bank of about $14,000 as well as gross neglect of his duties of his state position.

Washington’s governor appeared to have been the beneficiary of some helpful radio coverage from KJR and it appeared that his office possibly figured in delaying or diminishing a much-needed review of the bank’s finances.

Edmund Campbell was fully involved in the financial shenanigans. In addition to his role in aiding Linden’s diversion of funds, he also was charged with improper financial matters at the Camlin Hotel whose penthouse he occupied. When he vacated the hotel after the ABC/NRS/Camlin financial debacle, he made off with more than $3,000 worth of hotel furnishings.

Puget Sound Savings and Loan was in the hands of a receiver but attempted to right its ship with W. C. Comer at the helm as president. He was convicted of misrepresenting the bank’s assets by falsifying a published statement.

Puget Sound Savings and Loan was bankrupt and liquidated – and its 27,000 depositors were left largely high and dry.

The financial transaction were exceedingly complex and could easily be a challenge for jurors to puzzle out. Because there were multiple business entities involved (American Broadcasting Company, Northwest Radio Service and its subsidiaries, Puget Sound Savings and Loan, the Camlin Hotel, Metropolitan Bank -where some ABC and NRS accounts were kept) abundant fund transfers had occurred between all of them – not to mention the personal accounts of the defendants.

The sums involved were hard to track. Linden was accused of having taken about $1,000,000 but $400,000 of that was in the form of dividends on his bank stock. Under banking regulations, the dividend payments were apparently proper although one could question the moral propriety of voting sizeable dividends when it was clear the bank was in trouble. Widely varying numbers kept floating around in the press and the courts. Linden took $40,000 in one day (in two different transactions) or he took $116,620 or he took $85,800 for ABC personnel on the same day but the law under which was being charged for the latter because of the way in which the funds were taken. While it was alleged he had improperly taken more than $500,000, he was actually charged with taking a significantly lesser amount.

It was dizzying and even now is hard to comprehend. By the time Linden’s radio empire was in full flourish, it was estimated to be costing about $13,000 per month to operate but generating only about $5,500 in revenue. In 2020 dollars that would be $190,000 in expenses versus $82,500 in income each month. The spread couldn’t have been easily ignored by those involved in its financial operations. It was the job of the extremely tenacious and determined prosecuting attorney, Robert W. Burgunder, to explain it all in court.

And at the center of it all was Adolph Linden.

He was fully cooperative in court, affable in demeanor and appeared at ease. At one point during a recess, he told a joke to the prosecuting attorney and his own defense lawyer at the side of the courtroom – and all three men burst out laughing.

Only once, while on the stand, did he become emotional. Moved nearly to tears, he expressed great remorse over the use of bank funds to construct the Camlin noting it was his biggest mistake. Otherwise, he believed he had done nothing wrong in his use of bank funds.

And it took three trials to convict him.

Linden didn’t believe himself to be guilty for two reasons. The most important was that, as his financial world was crashing down upon him, he turned over all of his assets to the bank to satisfy the deficiency. ALL of his assets. His stocks, bonds, cash, his elegant home and the library it contained (which was one of the finest in the nation), his car, his radio stations, his network and all of Elizabeth’s assets as well – everything he had and was enough to make the bank whole.

Linden had used the bank rather like a petty cash fund (although the sums were hardly petty). In his own mind he had sufficient assets to cover everything he had taken so, in Linden’s interpretation, he was using bank funds to cover losses with the expectation that income from the radio business would grow sufficiently to pay it all back. And should that not prove to be the case, he had sufficient wealth to pay it back himself. He certainly didn’t see himself as either an embezzler or a thief.

Linden’s misfortune was that, while he turned over these assets to the bank, it didn’t quickly liquidate them. When the October Stock Market Crash sufficiently devalued them, they were insufficient to cover the bank’s losses.

Two hung juries seemed to agree with that interpretation. However, prosecuting attorney Burgunder was determined. Whether the fact that in King County the prosecuting attorney was an elected office had anything to do with his fierce determination to see Linden convicted is unknown.

There was more than enough blame to go around. The state banking inspector, Wallace L. Nicely, was serving on Puget Sound Savings and Loan board while simultaneously serving as the regulatory official with responsibility for overseeing the bank. He was charged with both this having defrauded the bank of about $14,000 as well as gross neglect of his duties of his state position.

Washington’s governor appeared to have been the beneficiary of some helpful radio coverage from KJR and it appeared that his office possibly figured in delaying or diminishing a much-needed review of the bank’s finances.

Edmund Campbell was fully involved in the financial shenanigans. In addition to his role in aiding Linden’s diversion of funds, he also was charged with improper financial matters at the Camlin Hotel whose penthouse he occupied. When he vacated the hotel after the ABC/NRS/Camlin financial debacle, he made off with more than $3,000 worth of hotel furnishings.

Puget Sound Savings and Loan was in the hands of a receiver but attempted to right its ship with W. C. Comer at the helm as president. He was convicted of misrepresenting the bank’s assets by falsifying a published statement.

Puget Sound Savings and Loan was bankrupt and liquidated – and its 27,000 depositors were left largely high and dry.

The financial transaction were exceedingly complex and could easily be a challenge for jurors to puzzle out. Because there were multiple business entities involved (American Broadcasting Company, Northwest Radio Service and its subsidiaries, Puget Sound Savings and Loan, the Camlin Hotel, Metropolitan Bank -where some ABC and NRS accounts were kept) abundant fund transfers had occurred between all of them – not to mention the personal accounts of the defendants.

The sums involved were hard to track. Linden was accused of having taken about $1,000,000 but $400,000 of that was in the form of dividends on his bank stock. Under banking regulations, the dividend payments were apparently proper although one could question the moral propriety of voting sizeable dividends when it was clear the bank was in trouble. Widely varying numbers kept floating around in the press and the courts. Linden took $40,000 in one day (in two different transactions) or he took $116,620 or he took $85,800 for ABC personnel on the same day but the law under which was being charged for the latter because of the way in which the funds were taken. While it was alleged he had improperly taken more than $500,000, he was actually charged with taking a significantly lesser amount.

It was dizzying and even now is hard to comprehend. By the time Linden’s radio empire was in full flourish, it was estimated to be costing about $13,000 per month to operate but generating only about $5,500 in revenue. In 2020 dollars that would be $190,000 in expenses versus $82,500 in income each month. The spread couldn’t have been easily ignored by those involved in its financial operations. It was the job of the extremely tenacious and determined prosecuting attorney, Robert W. Burgunder, to explain it all in court.

And at the center of it all was Adolph Linden.

He was fully cooperative in court, affable in demeanor and appeared at ease. At one point during a recess, he told a joke to the prosecuting attorney and his own defense lawyer at the side of the courtroom – and all three men burst out laughing.

Only once, while on the stand, did he become emotional. Moved nearly to tears, he expressed great remorse over the use of bank funds to construct the Camlin noting it was his biggest mistake. Otherwise, he believed he had done nothing wrong in his use of bank funds.

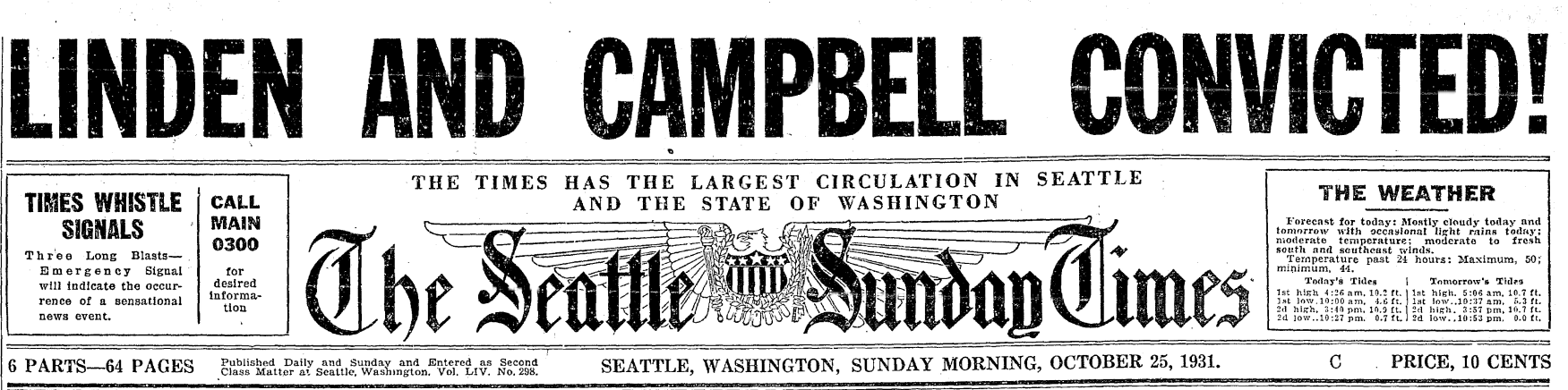

And it took three trials to convict him.

Linden didn’t believe himself to be guilty for two reasons. The most important was that, as his financial world was crashing down upon him, he turned over all of his assets to the bank to satisfy the deficiency. ALL of his assets. His stocks, bonds, cash, his elegant home and the library it contained (which was one of the finest in the nation), his car, his radio stations, his network and all of Elizabeth’s assets as well – everything he had and was enough to make the bank whole.

Linden had used the bank rather like a petty cash fund (although the sums were hardly petty). In his own mind he had sufficient assets to cover everything he had taken so, in Linden’s interpretation, he was using bank funds to cover losses with the expectation that income from the radio business would grow sufficiently to pay it all back. And should that not prove to be the case, he had sufficient wealth to pay it back himself. He certainly didn’t see himself as either an embezzler or a thief.

Linden’s misfortune was that, while he turned over these assets to the bank, it didn’t quickly liquidate them. When the October Stock Market Crash sufficiently devalued them, they were insufficient to cover the bank’s losses.

Two hung juries seemed to agree with that interpretation. However, prosecuting attorney Burgunder was determined. Whether the fact that in King County the prosecuting attorney was an elected office had anything to do with his fierce determination to see Linden convicted is unknown.

At Linden’s third trial the defense again attempted to present the same argument about why what Linden did wasn’t criminal and his conduct didn’t meet the test for a criminal act – but the judge refused to allow that line of defense to be presented. Indeed, when this third jury appeared to be deadlocked, the judge brought them into the courtroom and gave the jury a new, exceedingly narrow instruction which so tightly narrowed the range under which “motive” could be considered so as to virtually instruct the jury to find Linden guilty. Burgunder had argued that, regardless of whether Linden had sought to, or actually did, reimburse the bank, the initial act of taking the funds was itself a criminal violation requiring conviction.

When the defense objected to what it contended was a highly unusual procedure on the judge’s part and was overruled, the jury did as “instructed”. They returned a “guilty” verdict. One juror who had actually lost her own savings in the bank’s failure cried – and she was still crying when she left the courthouse after the jury was dismissed.

Different jurisdictions now vary in their treatment of white-collar criminal embezzlement when restitution is made before criminal charges are filed. Sometimes an embezzler is freed and put on probation. Sometimes a lighter than normal sentence is imposed. And sometimes it makes no difference at all. In Linden’s case the judge attempted to impose a harsher sentence than the law actually permitted and it was Bergunder who corrected the judge who then imposed the maximum the law allowed.